Lvov, whom I saw once or twice at sessions of the Council of Ministers during my time as Commander in Chief of the Petrograd Military District, came to me; I knew he was a member of the State Duma and Chief Procurator of the Synod. Lvov announced to me, on behalf of Kerensky, that if I believe his (Kerensky’s) further involvement in running the country will not give the regime the strength and resolution needed, then Kerensky is prepared to leave the government. See more

Also attending: Kerensky, Catherine Breshkovsky, KornilovCommander in Chief of the Petrograd command - from 18 March 1917, Nekrasov, Lvov, Rodzianko, Tsereteli, Guchkov, Plekhanov, Trubetskoy and others

The “breach of the revolutionary army”, reported on by the head of the government, “War Minister”, Prince Lvov " ended in treason by the Grenadier Guards. The entire Eleventh Army, abandoning their positions, went running into the rear after them. See more

It was a nice, hot day. I went around the park with Tatiana and Plarie. During the day I worked with them in the same place as before. Yesterday and today the guards from the 1sti and 4th, Infantry Regiments were punctual in their performance and were not roaming around in the garden as we took our walk. See more

When I was leaving the capital, trucks began flashing by on Petrograd streets, full of unknown armed people. Some were driving around the barracks, calling soldiers to join the armed revolt that was expected at any moment. One gang infiltrated the yard of the Ministry of Internal Affairs and broke into the first floor, where the office of Duke Lvov was located, which I have just left. See more

The government will under no circumstance agree to Ukrainian claims before the Constituent Assembly is convened. The autonomy of the Ukraine is a matter that concerns the entire Russian people. The Provisional Government received its power from all nations, and cannot take responsibility for the dissolution of Russia.

When I reached the Finland Station this morning, I found Sazonov by the carriage which had been reserved for us. In grave tones he said to me:

"All our plans are changed; I'm not coming with you. . ... Read this!"

He gave me a letter, dated the same night and just put in his hands, in which Prince Lvov asked him to postpone his departure as Miliukov had sent in his resignation.

"I go and you stay behind," I said. "Isn't it symbolical?" See more

The soul of the Russian people has proven in its very nature to be a global democratic soul. It’s ready not only to merge with the democracy of the entire world, but also to assume a position of leadership and to lead it down the path of human progress as inspired by the great principles of freedom, equality and brotherhood.

Milyukov and Shingaryev went to the front. While they were gone, a Provisional Government meeting was unexpectedly called late one evening in Prince Lvov's apartment. Kerensky and Tereshchenko took it upon themselves to sharply attack the point about the Straits and Milyukov’s entire role in the Provisional Government. I was the only one to stand up for him. See more

We can count ourselves as the luckiest people, because our generation was born into the happiest period of Russian history.

We needed, by all means, a strong power. This is power that prince Lvov did not bring with him.

If we’re going to have universal suffrage, what’s the rationale for preventing women who wish to participate in elections from doing so? Our electoral law is being developed. In its final form, it is contingent on the total composition of the provisional government. But I’m for the participation of women.

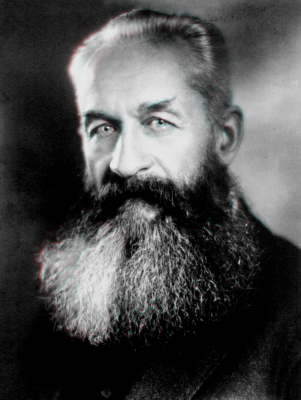

IT was Prince Lvoff who arranged my first meeting with Kerensky. I could not have had a better introduction. Like most Socialists Kerensky admired and respected Lvoff as much for the integrity of his character as for the work he had done for the Russian people. I received an invitation to luncheon.

At the appointed hour my sleigh drew up before the Ministry of Justice, and I climbed up the long steps of the official staircase, where only three weeks before had reigned all the rigid ceremonial of the ancient régime, into an ante-chamber filled with a crowd of soldiers, sailors, legal functionaries, students, schoolgirls, workmen and peasants, all waiting patiently like one of the bread queues in the Liteinaia or the Nevsky. I pushed my way through the throng to a tired and much-harassed secretary.

"You wish to see Alexander Feodorovitch Kerensky? Quite impossible. You must come tomorrow."

I explain patiently that I am invited to luncheon. Again the machine-like voice breaks in: "Alexander Feodorovitch has gone to the Duma. I have no idea when he will be back. In these days you know... ."

He shrugs his shoulders. Then, almost before I have time to allow the disappointment to show on my face, the crowd surges forward. "Stand back, stand back," shout the soldiers. Two nervous and very young adjutants clear a passage, and in half a dozen energetic strides Kerensky is beside me. His face has a sallow and almost deathly pallor. His eyes, narrow and Mongolian, are tired. He looks as if he were in pain, but the mouth is firm, and the hair, cropped close and worn en brosse, gives a general impression of energy. He speaks in quick, jerky sentences with little sharp nods of the head by way of emphasis. He wears a dark suit, not unlike a ski-ing kit, over a black Russian workman's blouse. He takes me by the arm and leads me into his private apartments, and we sit down to luncheon at a long table with almost thirty places. Madame Kerensky is already lunching. By her side are Breshkovskaia, the grandmother of the Russian Revolution, and a great brawny-armed sailor from the Baltic Fleet. People drift in and out at will. Luncheon is a floating meal and it seems to be free to all. And all the while Kerensky talks. In spite of the Government prohibition order there is wine on the table, but the host himself is on a strict diet and drinks nothing but milk. Only a few months previously he has had a

tubercular kidney removed. But his energy is undiminished. He is tasting the first fruits of power. Already he resents a little the pressure that is being put on him by the Allies. "How would Lloyd George like it if a Russian were to come to him to tell him how to manage the English people?" He is, however, good-natured. His enthusiasm is infectious, his pride in the revolution unbounded. "We are only doing what you have done centuries ago, but we are trying to do it better – without the Napoleon and without the Cromwell. People call me a mad idealist, but thank God for the idealists in this world!' And at the moment I was prepared to thank God with him.